"Report on the Cholera Outbreak in the Parish of St. James, Westminster, during the Autumn of 1854"

(July 1855)"Presented to the Vestry by the Cholera Inquiry Committee."

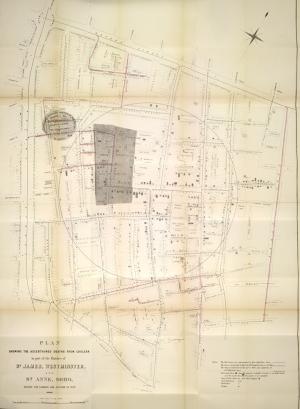

[Thanks to MATRIX staff who undertook electronic transcription, initial copy-editing, and the insertion of some images. I have added images of the General Board of Health map published in conjunction with the special report by Fraser, Hughes, and Ludlow. The Cholera Inquiry Committee inserted an impression of this map (divided in two parts) between pages 96 and 97 of its report. In addition, they used colors to distinguish the two phases of recent sewer construction and added a circle to distinguish the cholera field.—PVJ.]

Introduction.

The Rev. H. Whitehead's Report.

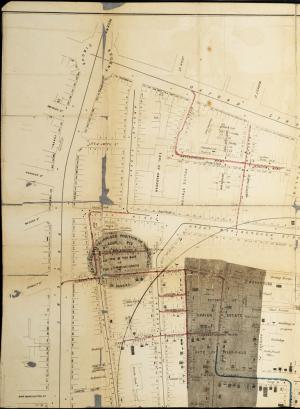

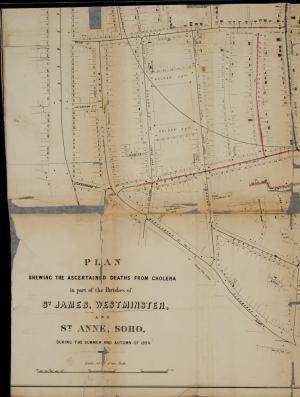

This Map is the same as that which illustrates the Report of Messrs. Fraser, Ludlow and Hughes on the Cholera outbreak in this district. It is founded on the Map published in Mr. Cooper's Report to the Commissioners of Sewers; but St. Anne's Court and the neighbourhood have been added to it, and the fatal attacks which occurred in the district throughout the whole epidemic have been inserted in their respective localities where these could be accurately determined. Further explanations are given on the Map.

[ii/iii]

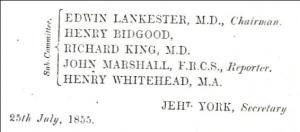

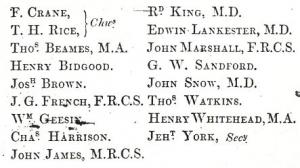

The Cholera Inquiry Committee appointed by the Vestry of St. James's, Westminster, upon the motion of Dr. Lankester, seconded by Mr. Joseph Brown, "for the purpose of investigating the causes, arising out of the sanitary condition of the Parish, of the late outbreak of Cholera in the districts of Golden Square and Berwick Street," entered upon its duties on November 25th, 1854; and, having held altogether fourteen meetings, completed its labours on July 25th, 1855, by adopting the accompanying Report.

Including certain members added at different times to its original number, the Committee finally consisted of the following Gentlemen:--

Messrs. Crane and Rice, the Churchwardens.

*Rev. T. Beames.

Mr. Bidgood.

Mr. Brown.

*Mr. French.

Mr Geesin.

Mr. Harrison.

*Mr. James

*Dr. King.

Dr. Lankester.

*Mr. Marshall.

*Mr. Sanford.

*Dr. Snow.

Mr. Watkins.

*Rev H. Whitehead.

[iii/iv]

Mr. York was requested to undertake the duties of Secretary.

For the purposes of this inquiry the Committee availed itself of the following sources of information. 1.--The Report of the Committee of Health and Sanitary Improvement appointed by the Vestry of St. James's in 1848. 2.--A Report by Mr. E. Cooper to the Metropolitan Commissioners of Sewers on the state of the Drainage in the localities affected by Cholera, containing a map of the Sewers, &c., September 1854. 3.--The Rev. Henry Whitehead's narrative, entitled "The Cholera in Berwick Street," 1854. 4.--Report on the Well Waters of the Parish of St. James, by Dr. Lankester, 1854. 5.--Dr. Sutherland's Report on Epidemic Cholera in the Metropolis in 1854, published in January 1855. 6.--Various Returns issued under the authority of the Registrar-General.

Besides consulting these published documents, the Committee obtained from the office of the Registrar-General a Return of the House-population in the districts of Golden Square and Berwick Street, according to the Census of 1851; and from the local Registers [probably the Registrar General's sub-district Registrars], through Mr. Buzzard the Vestry Clerk, [iv/v] as well as from various Hospitals, documents to aid in forming an estimate of the extent and severity of the epidemic.

An early application was also made to Sir B. Hall, the President of the General Board of Health, for such information as might be at his disposal, relating to the Cholera outbreak in this Parish, but, principally on the ground that investigations of this kind were more valuable when independent, the President did not comply with this request.

More recently, in conjunction with Messrs. Fraser and Ludlow, two of the local Inspectors appointed by the Board, a deputation from the Committee endeavoured to construct as correct a chart of the deaths in the affected districts as could be made. By permission of the Board, the Committee has been enabled to obtain from the Lithographers some impressions of this map to illustrate the present Report.

The first attempt of the Committee to collect local information in the Cholera districts was by means of a printed Inquiry Return distributed to each house, with a request that it might filled up by the occupier. This measure did not produce the anticipated results.

At the desire of the Committee, Dr. Snow, [v/vi] on December 12th, 1854, laid before it a Report, containing an account of his researches already made on the supposed influence of the well water from the public pump in Broad Street, in producing the Cholera outbreak in its neighbourhood. The Committee have considered this document sufficiently important to be added at length to its Report.

A subsequent attempt to obtain local information, by a house to house visitation, was more successful. By the assistance of a printed form, or "Visitors' Inquiry List," prepared by Drs. King, Lankester, and Snow, the following streets were visited by the under-mentioned members of the Committee:--The Rev. Thomas Beames, Mr. James, Dr. King, Dr. Lankester, Mr. Marshall, Mr. Sandford, Dr. Snow, and the Rev. H. Whitehead, viz.:--Broad Street, Marshall Street, Bentinck Street, part of Berwick Street, Kemp's Court, Peter Street, Green's Court, Husband Street, Hopkins Street, New Street, Pulteney Court, Cambridge Street, and part of Silver Street, containing in all 316 houses.

This "Visitors’ Inquiry List," a copy of which will be found in the Appendix, contained twenty-two heads or subjects of investigation, on each of which exact information [vi/vii] was desired. The lateness of the inquiry,––the departure of many families from the neighbourhood,--the imperfect recollection of some,--the reluctance to reply on the part of others,--and the impossibility of underground research,--are circumstances which all interfered with the completeness of this local investigation. Its results, which may serve as a guide in any subsequent inspection, have been tabulated by the Secretary, in a form corresponding with that adopted by the Committee of Health and Sanitary Improvement in 1818.

In the hands of one member of the Committee, the Rev. H. Whitehead, whose previous knowledge of the district both before and during the epidemic, owing to his position as Curate of St. Luke's, Berwick Street, gave him unusual advantages, the Visitors' Inquiry elaborated itself into a most minute and painstaking investigation of a principal street, situated in the very heart of the locality affected. His special Report upon Broad Street the Committee have thought it necessary to append at length.

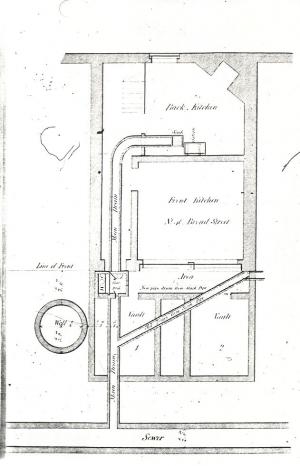

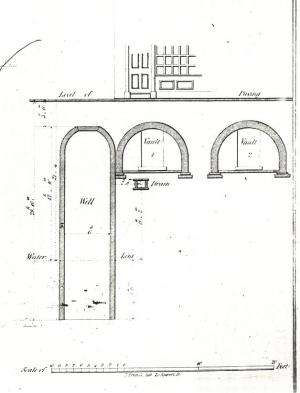

In consequence of facts ascertained by Mr. Whitehead, instructions were given to the Secretary, Mr. York,--whose practical experience entitles his evidence to complete [vii/viii] acceptance,--to inspect the cesspool and drains of the house, No. 40, in Broad Street, close to which the public pump is situated, and also to open and examine the well itself and the soil intervening between it and the drains and cesspool. Mr. York's statement, accompanied by a plan and section, is also annexed to this Report.

The analysis of six specimens of surface well water, the composition of which it was desirable to ascertain, was conducted in the Birkbeck Laboratory, at University College, by Messrs. Powell, Ormsby, Smith, and Worsley, at the request of Professor Williamson.

Lastly, many of the facts and statements in the following pages depend on the authority of individual members of the Committee.

The drawing up of the Report was entrusted to Mr. Marshall.

It is arranged under the four following heads:--

1. History of the outbreak.

2. Circumstances attending the outbreak.

3. Hypotheses concerning the outbreak.

4. Recommendations of the Committee to the Parochial Authorities.

[viii/9]

The Parish of St. James, Westminster, occupies an area of 164 statute acres. At the census of 1831, it contained 37,053 inhabitants; in 1841, 37,457; and in 1851, 36,406. Its population may therefore be said to be nearly stationary; the small diminution since 1841 being probably owing to public improvements, especially to those made in connection with the building of the Museum of Economic Geology in Jermyn Street.

For the purposes of Registration, the Parish is divided into three sub-districts, viz. St. James's Square sub-district, occupying 85 acres, with a population of 11,469; Golden Square sub-district, extending over 54 acres, and numbering 14,139 inhabitants; and Berwick Street sub-district, having an extent of 25 acres, and a population of 10,798. Since 1841, the population of St. James's Square sub-district has decreased, whilst that of the other two districts shews a slight increase.

The parish is immediately surrounded by the following registration sub-districts :--May Fair and Hanover Square, in St. George's Parish, on the West; All-Souls, Marylebone, on the North; St. [9/10] Anne's, Soho, on the East; and Charing Cross, in St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, on the East and South.

1832. In the first visitation of Cholera in 1832, the parish of St. James, then numbering 600 more inhabitants than in 1851, suffered in only a moderate degree in comparison with many others, and on the whole somewhat later in point of time. The earliest deaths in the parish took place in March, and then the epidemic, subsiding until July, reappeared and continued during August, September and October. The total number of deaths occasioned by it cannot now be determined. About 90 cases fell under the observation of the parochial medical officers, of which number half proved fatal. To these would have to be added the deaths occurring in private practice. On the authority of Messrs. Braine and French, who at that time had medical charge of the Cholera Hospital, it may be stated that among the localities attacked were Peter Street, Hopkins Street, Maidenhead Passage, Pulteney Court, Berwick Street, Wardour Street, Broad Street and Carnaby Street, together with the courts and yards leading out of Great Windmill Street, the neighbourhood of St. James's Market, and also Angel Court and Crown Court, Pall Mall. At this period the general sanitary condition of the parish was doubtless defective; for attention was not then so strongly directed to questions concerning the public health. At the commencement of 1848, the Committee of Health and Sanitary Im-[10/11]provement detected and exposed, by their house visitation, numerous deficiencies in local cleanliness, especially in the public sewerage. In consequence of these inquiries a decided amelioration of such defects was accomplished; and it was a subject of congratulation amongst those who were interested in the health of the parish, that the epidemic of 1848-9, which so speedily followed, was even less severely felt by the inhabitants than the visitation of 1832.

1848-9. During the autumn of 1848 only three deaths from Cholera occurred in St. James's, viz. one each in Berwick Street, Poland Street, and Rupert Street. In the first four months of 1849 no fatal case occurred in the parish, although, from the middle of January to the middle of February, the effects of Cholera were plainly manifested all over London. On the 26th of May, one fatal case happened in Golden Square. In July, five deaths were registered, and the disease, continuing through August and September, proved fatal altogether to 56 persons, viz. 19 belonging to Berwick Street district, 19 to Golden Square district, and 18 to St. James's Square district. Seventeen additional deaths were registered from Diarrhœa: Thus the mortality from Cholera in the whole parish in 58 weeks of 1848-9 was about 15 in 10,000 persons living, whilst the corresponding rate in all London was 75, and in the immediately surrounding districts about 46. In St. Anne's, Soho, the relative mor-[11/12]tality was 30 to 10,000 persons living; and of 48 deaths which occurred in that parish, to a population of 16,480, only five took place in St. Anne's Court, then containing about 500 inhabitants. This visitation of 1848-9 commenced about the same period in St. James's as in the adjoining parishes, shewing itself earliest in the Golden Square district, next in the Berwick Street, and last in that of St. James's Square, but reaching its height in all three about the same period, and causing its greatest mortality in the weeks ending the 1st and 8th of September, corresponding in this respect with the general result throughout the metropolis.

The streets which suffered most were the following:--In the Berwick Street district, Peter Street (four deaths), Archer Street (two), and Pulteney Place (two); in the Golden Square district, the Workhouse (five inmates), Regent Street (two), South Row (two), and Little Windmill Street (two); in the St. James's Square district, Angel Court (six), Jermyn Street (three), Little St. James's Street (two), Great Windmill Street (two), and Queen's Head Court (two). The rest of the mortality consisted of single deaths in various streets. No fatal case occurred in Broad Street in 1848-9, although a man died of Diarrhœa at No. 6.

1850. Four fatal cases of Cholera are recorded during this year in the following localities:--Silver Street, Carnaby Street, Marshall Street, and Oxford Street.

[12/13]

1851. In this year one case is registered in Rupert Street.

1852. A single death is returned at 5, Marshall Street.

1853. During the last four months of 1853, when Cholera for the third time invaded the metropolis, ultimately to become epidemic, several fatal attacks occurred in St. James's parish, as follows:--In August, one case occurred in Great Windmill Street, and another in Bentinck Street. The next death, on October 2nd, was in Poland Street. After a short interval, five cases followed in one week, viz. three in the Workhouse on October 26th and 30th, and November 1st; two in Marlborough Court, October 30th; one in King Street, on the 31st October; and one in Great Marlborough Street on the 1st November. On the 4th November another fatal attack happened in the Workhouse; and the last death for the year 1853 was in Blenheim Street, on November 15th.

It is important to remember these successive visitations of Cholera in St. James's parish, and especially the presence of the disease during the autumn of 1853; for they serve to establish its liability to the inroads of that epidemic, although they entirely failed to prepare its inhabitants for the impending calamity of 1854.

1854. At the commencement of this year, there were but five deaths from Cholera registered throughout the whole of the metropolis during [13/14] the month of January; in February, only two, the last being on February 4th. For the eight succeeding weeks no fatal case was registered in London. During the month of April four deaths occurred. Three weeks passed without a death from Cholera, and then four happened in the latter part of May. In the first three weeks of June three deaths occurred, in the fourth week no death. In the first week of July one death was registered, in the second week 5 deaths, in the third 26, in the fourth 133, in the fifth 399; and so the numbers kept increasing weekly up to 2,050 in the week ending September 9th, and then diminished again, as shewn in the subjoined table. The mortality from Cholera, in all London, was reduced to 8 in the week terminating the 8th of November.

Now, according to the Registrar-General's returns, no death from Cholera took place during last year in St. James's parish until the week ending the 5th August, when one fatal case was returned. From this date the Cholera mortality in the parish rose and fell as shewn in the annexed table, in which the corresponding mortality in all London, and that in London exclusive of St. James's, is also shewn.

[14/15]

Adding to this list one more death which was recorded in the St. James's Square district in the week ending October 21st, the total number of deaths from Cholera registered in St. James's, in the 17 weeks ending November 4th, was 484. But this number gives a very inadequate idea of the entire loss inflicted by the epidemic. Thus the House List of deaths by Cholera, furnished to the committee by Mr. Buzzard, the vestry clerk, from the local registers, gives a total of 501 deaths recorded between July 1st and September 30th. Besides these, it is estimated that about 150 of the inhabitants died during the same period in the Middlesex, University College, Royal Free, St. George's, and King's College Hospitals, out of the parish, whose deaths would therefore be registered elsewhere. It would appear, indeed, from the investigations of Messrs. Fraser, Hughes, Ludlow and Whitehead, that some deaths must have escaped registration altogether, and that possibly more than 40 non-resident persons, who came to work or visit in the parish, also died. Hence the fatal attacks in St. James's parish were probably not less than 700.

So great a number would imply a relative mortality, during the above defined 17 weeks, of 220 to every 10,000 persons living in the parish, instead of 152 as estimated upon the data furnished to the Registrar's Office. The highest relative mortality in any metropolitan parish not containing a hospital, [15/16] during the same period, was in Bermondsey, viz. 158. St. Olave's alone, which includes St. Thomas's Hospital, exceeded it, its ratio being 162. In the adjoining sub-district of Hanover Square, the ratio was 9; in All-Souls, Marylebone (including a hospital), 28; in St. Anne's, Soho, 37; and in the Charing Cross district of St. Martin's-in-the-Fields (including a hospital) 33. It should also be borne in mind that the mortality from Cholera in St. James's parish in 1848-9 was, as already stated, only 15 in 10,000 inhabitants.

It is well known, however, that the epidemic did not act equally within all parts of the parish; the St. James's Square sub-district experiencing, according to the Registrar, a relative mortality of only 16 to every 10,000 persons living, whilst the ratio in the Berwick Street district was 212, and in the Golden Square district 217.

But, as before stated, the actual rate beyond the registration returns, in the two last named districts, was considerably greater than this. Moreover, it must now be remembered that it was only in a certain singularly well defined portion of them that the influence of the great outbreak was felt. The "Cholera area," as it may be called, of St. James's parish, may be variously described. Reference to the map prefixed to this Report will render the description easily understood. Spreading out from the north-east angle of Golden Square, which is altogether excluded from it, it extends [16/17] westward to King Street, north as far as Great Marlborough Street and Noel Street, east to the line of Wardour Street, and south to Little Pulteney Street, from the west end of which its limit are expressed by a line crossing over Great Pulteney Street and Bridle Lane, returning to the northeast angle of Golden Square. Beyond Wardour Street, to the east, lies St. Anne's Court, Soho, with its dependencies, which, though out of St. James's parish, must be included in the Cholera area. It has been shewn by Mr. Whitehead that the limits of the Cholera district are also very accurately defined within an irregular four-sided figure, the north and south angles of which are placed respectively near the middle of Poland Street and at the south end of Little Windmill Street, whilst the west and east points are at the northwest corner of King Street and the east end of St. Anne's Court. The included space is rather longer from east to west than from north to south. The centre of this figure falls at the junction of Cambridge Street with Broad Street, and it has been remarked by Mr. Whitehead, as may be shewn with compasses upon the map that a circle, having a radius of 210 yards, struck from the northwest angle of Cambridge Street includes almost the entire area, except St. Anne's Court.--Two notches vacant of mortality require, however, to be taken out of this circle; one corresponding with a part of Great Marlborough Street, the other with one half of Golden Square and the southern part of Bridle Lane. As [17/18] thus defined and henceforth in this Report intended to be understood, the "Cholera area," including St. Anne's Court, and excluding the vacant spaces just mentioned, covers nearly 30 acres of ground, containing, besides streets, courts, and mews, 825 dwellings, St. Luke's Church, Craven Chapel, the Workhouse, a block of model lodging houses (unfinished in 1854), a brewery, and various factories and workshops. In round numbers, its population, in the autumn of 1854, as well as can be estimated, was nearly 14,000 inhabitants (inclusive of 500 in the Workhouse). This would be about 460 persons to an acre. Now the ascertained deaths of residents within this "Cholera area" are 618, being at the rate of 440 to 10,000 persons living. The deaths of non-residents, so far as these are known, viz., 45, are also indicated on the map.

The ascertained deaths and percentage of mortality in the several streets within the Cholera area are tabulated in the Appendix, whilst the distribution of the deaths is represented in the map. No street in the Cholera area was without death, but the mortality was greatest towards the centre of the area, and diminished towards its borders. There are exceptions, depending mostly on an extreme mortality in some one house in a small street, as in Cross Street on the west, Bentinck Street on the north, and Peter Street on the southeast. In Hopkins Street, then containing only three houses, the mortality was 18 per cent. In [18/19] Broad Street, the very heart of the area, the deaths were rather more than 10 per cent, or 1,000 to every 10,000 persons living. In Cambridge Street, Pulteney Court, and Kemp's Court, the population was also decimated. In Marshall Street, South Row, Marlborough Row, Silver Street, Great Pulteney Street, Little Windmill Street, the southern portions of Wardour, Berwick and Poland Streets, the mortality diminished, varying from 8 to 5 per cent; and, taking a still wider sweep from the centre, in the remoter parts of all these longer streets, as a rule, it gradually ceased. It will also be seen, on consulting the map, that in the centre of the Cholera area but few houses escaped the invasion of the disease. Of 45 contiguous houses belonging to Pulteney Court, New Street, Husband Street, Hopkins Street, and the south side of Broad Street, only seven escaped without a death; and in 3 of these seven, one a factory, 18 non-residents were fatally seized. In Broad Street, containing 49 houses, only 12 houses escaped without a death.

So also the proportion of houses fatally attacked, just as we have seen in regard to the per centage of deaths, became less in passing from the centre of the Cholera area. In the whole area, including houses where non-residents were seized, this proportion was 38.8 per cent.

Of the 825 houses in this area, fatal attacks of residents occurred in 313. There were 159 houses having single deaths; 85 with 2 deaths; 34 with 3; 15 with 4; 12 with 5; 3 with 6; 4 with 8; [19/20] and 1 with 12. Five inmates also died in the Workhouse. "There were," says Mr. Whitehead, speaking of only a part of the area, "no less than 21 instances of husband and wife dying within a few days of each other. In one case, besides both parents, 4 children also died. In another both parents, and 3 of their 4 children. In another a widow and 3 of her 4 children. At an average distance of 15 yards from St. Luke’s Church stand 4 houses which collectively lost 33 persons."

Such being the locality of this serious visitation, and such its general results, we may in the next place attempt to trace, within the limits of the Parish, its commencement, progress and cessation, from day to day, and from place to place. For this purpose, it is obvious that, owing to the variable duration of the illness, the death statistics would lead to erroneous conclusions; and it is much to be regretted that no complete data can be obtained for fixing the hour of attack. By deducting the period assigned to the duration of the disease from the day of death, where such information is recorded either in the registrar's or hospital documents, a rude approximation to the period of attack may be obtained. In regard especially to Cholera, this method may give tolerably fair results; but when we remember the difficulty of obtaining correct information and the importance of a few hours more or less, too great reliance must not be placed upon such results, nor too great use [20/21] made of them, as the foundation of particular views. In the Table placed in the Appendix, 576 fatal cases in St. James's and St. Anne's are arranged to shew the streets in which they took place and days on which the deceased are presumed to have been attacked. This tabular view of daily attacks is of course incomplete, and would differ widely from one of daily deaths. It is confessedly a partial view or an imperfect journal of the progress of the epidemic; but in its general aspect it may approach the truth. For convenience of reference, the streets are classified in four zones, or belts, running east and west across the parish, beginning with the northern zone from west to east, and then proceeding with the next one to the south, and so on. Only the two middle zones pass through the Cholera area.

The earlier deaths from Cholera in the metropolis last summer [1854] were scattered very widely about, in the extreme south, east, west and north,--the central districts escaping for a brief period. The first fatal attack in St. James's parish occurred on July 26th, in St. James's Market, Jermyn Street. It terminated fatally on the 29th, by which date 81 deaths had been registered in the south, 48 in the east, 11 in the west, 11 in the north, and 13 in the central metropolitan districts. It may therefore be said that the Cholera in the summer of 1854, as well as of 1849, shewed itself in this parish later than in most parts of the metropolis; and in reference to the immediately adjoining districts it must be added, that [21/22] St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, St. Anne's Soho, and All-Souls Marylebone, were attacked before, and St. George's Hanover Square after, St. James's.

Referring now to the Table, it will be seen that shortly after the first case already spoken of as happening on July 26th in the south of the parish, viz. in St. James's Market, two fatal attacks occurred in the west and centre, viz. in South Row on the 3rd August, and in Silver Street on the 5th. By the time these three attacks had occurred many more deaths had been recorded in the various districts of the metropolis, as follows:--south districts 371, east 108, west 33, north 23, and central 27. The fourth fatal seizure in St. James's was on the 7th, in the south, in Great Windmill Street; the fifth and sixth, both on the 11th, were in the west, viz, in King Street and Marlborough Row. On the following day, three persons were fatally attacked, two in the south and southeast of the parish, viz. in Piccadilly and Great Windmill Street, and one in the very centre of the district to be presently rendered so memorable, viz. in Broad Street, at No. 31. On the 14th, one seizure occurred in the west, in Heddon Court; and on the same day two near the centre, viz. in Silver Street and Marshall Street. On the 16th, two persons were attacked in Berwick Street, and one in Swallow Street; on the 17th, one in Marlborough Street; on the 18th and 19th, two persons in Marshall Street; on the 18th a man in Piccadilly, and on the 19th a man in Berwick Street. The deaths in Marshall Street were [22/23] in one house (the first being introduced from the Borough), and two of those in Berwick Street were also in one dwelling. During this week Diarrhœa was very prevalent all through the Berwick Street district and the adjacent part of the Golden Square district; but in the eleven following days, until the 30th August, Diarrhœa had disappeared, and very few fatal attacks of Cholera occurred; these were either in the south or west, but chiefly towards the centre of the yet future Cholera area, viz. in Carnaby Street, Silver Street, Marshall Street and Broad Street. It appears, therefore, that the disease manifested its fatal effects first on the southeast, west, and east quarters, and afterwards towards the centre of the Cholera area. Up to this date (August 30th) 38 cases only had occurred throughout the entire parish; but in the afternoon of the 31st August, 31 fatal attacks can be traced. On the 1st September, 131, and on the 2nd, 125. On the 3rd, 4th, and 5th, the numbers are respectively 58, 52, and 26; and on the 6th, 7th, and 8th, 28, 22, and 14. After that attacks occurred as follows, 6, 2, 3, 1, 3, 0, 1, 3, 4; and subsequently throughout the rest of September either 1, 2, or 0 per diem. In Dr. Snow's report, the number of daily attacks is also fully and carefully reckoned, as his inquiry took place immediately after the eruption of the disease.

We have here a record of what has so forcibly struck the attention of those who have studied this [23/24] memorable eruption of Cholera, viz. the ordinary gradual approach of the disease accompanied by no unusual manifestation of its effects, a lingering about certain localities, a lull in its operation, and then, on a sudden, a terrible outburst, overwhelming every one by surprise, outstripping the most prompt and energetic attempts to mitigate its effects, and then quickly declining by well marked though not quite such speedy steps.

It is this startling suddenness of the outbreak that has given it a scientific interest, scarcely less momentous than its social importance; and as few of us probably will ever witness its like again, it is most desirable that no pains should be spared in its thorough investigation.

On consulting the Table in the Appendix, in which the distribution of a great majority of the attacks in the several streets is indicated day by day, it will be seen that the suddenness of the principal outburst, as also its rapid subsidence, is chiefly marked in those streets and courts which are nearest to the centre of the Cholera area; whilst in the borders of this space, and beyond its limits, there is no such abrupt and extreme rise and fall in the number of the attacks. In Broad Street especially its commencement was sudden and its duration short; but the disease continued somewhat later to attack a few persons in other localities.

On the whole, however, the great explosion was almost simultaneous throughout the district; and [24/25] even in the remotest streets, it must be remarked that though the attacks were few, the period of greatest activity corresponded with that of the principal outburst, and indeed with that of highest Cholera mortality throughout the rest of London (see Table, p. 14). There was, moreover, a small simultaneous outburst in Rotherhithe.

There yet remain several characteristics of this visitation, which may here be noticed, as tending either to associate it with or distinguish it from other less severe and sudden outbreaks of the disease.

In the first place it may be remarked, that in 1854, though the epidemic visited the same streets as in 1832 and 1848-9, it did not limit itself so precisely to its old localities as is often observed. A coincidence in the localities affected is perhaps more marked in regard to the straggling cases on the outskirts of and beyond the Cholera area than in the heart of that district. We are informed by Dr. Fraser that in the whole parish identical houses were visited in only 11 instances, out of about a total, as we estimate, of 350 in which fatal attacks occurred. On the contrary, entire streets in the centre of the affected area, as Broad Street, Silver Street, Cambridge Street, Pulteney Court and New Street, in which no deaths from Cholera occurred in 1848-9, suffered the most severely in 1854.

Certain apparent eccentricities or preferences of localization, such as are very common in Cholera visitations, displayed themselves here also. For [25/26] example, one side of a street would suffer more than the other. In streets running north and south, the dwelling-houses being about equal on the two sides, the east side sometimes suffered most; in streets running east and west, the south side was generally most affected. Cambridge Street and Little Windmill Street are exceptions to the former, and Silver Street to the latter statement. The order in which houses were attacked followed no definite rule.

Some narrow streets and courts suffered severely; others nearly or quite escaped, as Tyler's, Great Crown and Walker's Courts; whilst wide streets, as Broad Street itself, were heavily visited.

In St. Anne's Court, the middle houses suffered most; in some culs de sac, as Bentinck Street and Peter Street, those near the dead end.

The southeastern half of the Cholera area is a few feet lower than the northwestern half; but the mortality was not attached to any particular level.

A want of cleanliness in streets or houses was by no means a constant accompaniment of the disease. Some houses in the midst of others affected escaped, without any favourable sanitary condition. The map shews that, of houses in the Cholera area directly opposite untrapped sewer-grates, 40.2 per cent had fatal attacks in them, thus barely exceeding the general percentage throughout the area, viz., 38.8. Of two adjacent and equally well ordered factories, one lost seven workmen, the other none. Of nearly 200 workmen and women employed in another large factory, none living in the neighbourhood, the [26/27] females numbering about 160, the males about 30, sixteen of the former and two of the latter were fatally seized, whilst in the Workhouse, not 150 yards away, which had at the same time about 500 residents, only five inmates died. Of 35 men working in the open air on the unfinished lodging-houses, seven died.

Corner houses sometimes escaped, the 6 for instance on the north side of Broad Street, in one of which however there were 3 severe though not fatal attacks. Of corner houses in the Cholera area, about 30 per cent had fatal attacks in them. Public-houses, so often situated at the corners of streets, were singularly lightly visited.

As a general condition, remoteness from the centre of the Cholera area seems most to have been associated with exceptional suffering, and proximity to it by exceptional immunity, from the disease.

Towards the centre of the area, in Broad Street, the number of deaths appears to have been nearly equal on each floor, if we reckon the ground floors and kitchens together. In reference to the population, however, the ground floors suffered most; next, in diminishing proportion, the first floors, third floors, and kitchens, and least of all the second floors. Yet throughout the neighbourhood generally, including Broad Street, the deaths on the second floors were the most numerous of all. In the streets furthest removed north and south from the centre, the residents in the upper floors suffered somewhat more in proportion.

[27/28]

A calculation embracing the principal streets and courts shews that the number of deaths was rather greater in the front than in the back rooms of the houses.

The attacks in any given house were seldom quite simultaneous, commonly in quick succession, and more rarely at long intervals.

Tolerably true on the whole was this singular malady to its ordinary characteristics in the selection of its victims, whether we regard their occupations, general condition in life, sex, or age.

Of 636 registered deaths belonging to the parish, 298 were of males, and 338 of females, which is rather more females in proportion than usual. The ages of these deceased persons (with the exception of 6 unknown) were as follows:--

It appears therefore that, as usual with Cholera, the smallest number of deaths happened in the second decade of life. The fewest deaths in any one year of age (viz. two,) were between 14 and 15. The inmates dying in the Workhouse, were aged persons.

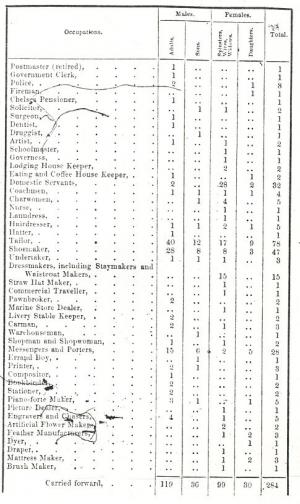

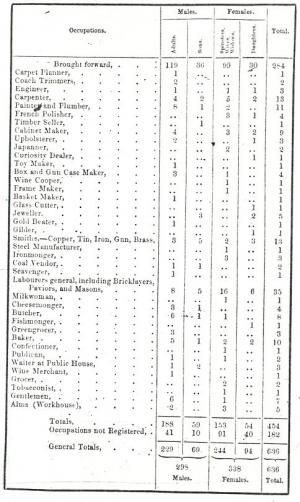

The occupations of 454 persons dying (247 male and 207 female) are indicated in the subjoined Table, constructed from the Registrar-General's returns. [28/29]

[29/30]

[30/31]

The total number of persons of any given occupation in the district is not known, so that the ratio of mortality in each must remain uncertain. A few general conclusions are evident. The families of tailors shew the largest number of deaths; next to these, shoemakers; then labourers, including bricklayers, masons, and paviors; then domestic, especially female, servants; next messengers and porters; then dressmakers; next follow mechanics of various kinds, as carpenters, smiths, painters, cabinet makers, and so forth. Of persons dealing in articles of food, bakers suffered most, and then butchers; whilst the families of greengrocers, publicans and fishmongers suffered less. General trades and the professions are also represented. It is necessary to observe that tailors and their families undeniably form a very large proportion of the working population of this district. On the whole it would appear that the disease did not limit its attack to any one class, nor yet to the very poor.

It is remarked by Mr. Sibley, the Registrar of the Middlesex Hospital, that a large number of the persons brought there for treatment presented a very uncleanly appearance; more so, indeed, than admitted into hospitals for ordinary disease. This may doubtless be explained, partly by the circumstances that the patients so admitted were probably the most destitute of those who were attacked, and partly by the fact of their being sud-[31/32]denly seized by the disorder whilst engaged in the usual occupations of their trade.

Finally, in this extraordinary outbreak, the symptoms of the disease quite corresponded with those of Cholera generally. The common occurrence of the attack within the fore part of the twenty-four hours, the extremely short duration of the early cases and the gradual amelioration observable in the later ones, were all plainly noticeable; and lastly, it is certainly true that in the cases occurring at the commencement of the great outburst, premonitory Diarrhœa was of short duration, or altogether absent.

It will have been noticed that the preceding estimate of the results of the Cholera outbreak in St. James’s parish is founded entirely on the death statistics. The number of attacks followed by recovery is unknown; nor can any certain information be collected as to the relative amount of Diarrhœa prevailing.

The sudden, severe, and concentrated character of the particular outburst of Cholera which has thus been depicted, and which constitutes the most [32/33] remarkable local visitation of that disease hitherto recorded in the metropolis, may at first create a hope that here at least the circumstances which principally determined the localisation of this singular epidemic would not escape a rigorous investigation. But the disadvantages attending a comparatively late inquiry, and the difficulties encountered in its prosecution were so great, that very decided conclusions must not be expected.

From our ignorance of the real or specific cause of Cholera, all inquiries like the present are practically limited to a consideration of those conditions which may determine the action of that cause upon and within certain localities. Further, it must be remembered, that in this comparatively restricted field of investigation, the want of knowledge just alluded to constitutes a grave difficulty. For if the cause of Cholera were itself as well understood as electricity, arsenic, prussic acid, or morphia, means could be found by which to determine its presence, qualities and quantity, and thus to lay bare, on positive evidence, the conditions which influenced its action, or cessation of action, in given places. But since we do not know the cause of Cholera, the questions to be solved concerning its appearance and disappearance, its spreading and concentration, can only receive provisional answers, approximating to the truth according as we have advanced, in the obscurity of our research, towards accuracy of observation, [33/34] correctness of deduction, and freedom from fallacy and error.

In attempting to analyse the circumstances which may be supposed to have had more or less influence in directing the terrible energies of this unknown cause towards a particular portion of the metropolis, we shall first examine the probable effect of those general conditions which must have operated in very much the same manner and degree in every part of it; such as the rainfall, the temperature and dryness and movement of the air. This will facilitate the subsequent examination of special or local conditions.

It has been pointed out by the Registrar-General, speaking of the metropolis generally, that "in the thirty-sixth week of 1854, when Cholera raged, and the deaths from all causes rose to their maximum (3413), the average daily range of temperature was 30.9° [F], considerably the greatest in the fifty-two weeks; the highest temperature of the week was 81.2°, the lowest was 43.1°, therefore the entire range was 38.1°; the horizontal movement of the air was only 195 miles, far less than any other week; there was no rain in that or the previous week, and the mean temperature of the previous week had risen to 65.1°, the highest mean weekly temperature in [34/35] the year." -- (Summary of Births, Deaths, etc., in London, for fifteen years, 1850-1854.)

This brief summary does not exhaust the interest attached to the general meteorological conditions prevailing in the metropolis during last summer and autumn, as especially applicable to our present inquiry.

Rain.--From the 6th August, when Cholera had fairly established itself in London, to the 11th September, when it had begun to decline,--i.e., for a period of 37 days,--there were only 7 days on which rain fell; the total quantity during that time being under three-tenths of an inch, one-third of which, i.e., one-tenth of an inch, fell in one day, the 15th August. From the 25th August to the 11th September (18 days), there was no rain at all, and it was within that period that Cholera manifested its greatest virulence.

Temperature of air.--From the middle to the end of July the temperature was excessive, and from thence to the end of September it was also decidedly above the average for that season of the year. Its maximum and mean daily value, and its daily range, stood very high on the 27th, 28th, 29th, and 30th of August, and on the 3rd, 4th, and 12th of September; the maximum temperature fluctuating from 80° to 85° degrees in the shade, and from 99° to 114° degrees in the sun; the three hottest days being the 27th, 28th, and 30th August, and on the 2nd, 5th, 6th and 7th Sep-[35/36]tember, the temperature, though not so high, was from ½° to 4° above the average calculated for 38 previous years. On the 1st September the temperature fell slightly, 6/10 of a degree below the average for that day, still however reaching to 72° in the shade and 94° in the sun. On the 27th, 28th and 29th August, there was more or less cloud and haze; but from the 30th August to the 6th September the sky was almost continually cloudless.

Temperature of water in the Thames.--During the months of July and August the mean temperature of the water at Greenwich was 64°; in September 63°. In the two weeks ending September 2nd it ranged from 60° to 68°.

Hygrometric state of the air.--As tested by the dew point, the air was drier than usual in the months of August and September. Compared week by week, its mean dryness increased and diminished somewhat like the mortality from Cholera; but examined daily during the latter part of August and the beginning of September extreme variations are recorded at Greenwich on any one day; and from the 30th August to the 6th September the lower atmosphere was not far from complete saturation at some period of each twenty-four hours.

Wind.--On the 26th August the wind, which for four weeks had been from S.W., W., or S., changed to N.W. On the next three days there was only occasionally a very gentle movement from the N. On the 30th, what wind there was, was N., and [36/37] then S.W. and W.S.W. On the 31st S.W., and then N.E. On the 1st September, N. On the 2nd, S.E. and E. From the 3rd to the 12th September, N.E., and after that S.W. again.

Horizontal movement of the air.--The stillness of the air during the two weeks ending September 2nd and September 9th, in which the mortality from Cholera rose to its height, was very remarkable,--the total horizontal movement for those weeks being not more than 245 and 195 miles. Now, during the ten years from 1845 to 1854, the average weekly movement was 783 miles, and the average for the year 1854 itself 687. Instead however of 100 miles a day, the average daily rate in the two Cholera weeks, as they might be called, was but little more than 30 miles. But even this is not an adequate account of the unusual stillness of the air; for during the 10 previous years, not 10 single weeks can be found in which the movement was less than 195 miles; and further, during the two weeks just indicated even the slight movement which did occur was not continuous, but interrupted by long intervals of calm. Thus, out of 16 days, from the 27th August to the 11th September, there were 11 days more or less calm; seven of these, viz. 27th, 28th and 29th August, and 1st, 4th, 10th and 11th of September, were calm throughout; and four, viz. 30th August, and 2nd, 7th, and 9th September, were calm during one half of the 24 hours.

[37/38]

Barometer.--Coinciding with this dry, hot, and quiet state of the atmosphere, the barometric range was continuously high, as would be expected.

Electricity and ozone.--The electricity, when observed, was positive and of moderate tension. The ozone action was defective or not manifested at all, a fact probably of serious import.

General conclusions.--From the preceding account it is plain that the period of greatest mortality from Cholera in the metropolis last autumn was characterised by a previous long-continued absence of rain, and by a high state of the temperature both of the air and of the Thames,--conditions which would render the waters of that river more concentrated as to impurity, favour periodical evaporation from its surface, and explain the alternating (diurnal and nocturnal?) extremes of dryness and saturation of the air. There was also an unusual stagnation of the lower strata of the atmosphere, highly favourable to its acquisition of impurity, to the operation of those partial currents which are caused by local variations of temperature, and to the more subtle movements dependent on the law of diffusion. Moreover, at the rise of the epidemic in London after the middle of July, it will also be found that somewhat similar conditions prevailed for many days; whilst at its decline they were all more or less changed; and although it is impossible to assert that the relations here pointed out were uniformly exact, or to fix the precise share which [38/39] each of the conditions enumerated might separately have in favouring the spread of Cholera, the whole history of that malady, as well as of the epidemic of 1854, and indeed of the plagues of past epochs, justifies the supposition that their combined operation, either by favouring a general impurity in the air, or in some other way, concurred in a decided manner during last summer and autumn to give temporary activity to the special cause of that disease.

If this supposition be correct, it is obvious that the same general meteorological conditions would operate simultaneously in the limited locality to which the present inquiry is directed; and here too we have found that the Cholera outbreak suddenly declared itself after the four hottest and calmest days of August, viz. the 27th, 28th, 29th and 30th. But, as previously shown in the history of this local outbreak, the resulting mortality was so disproportioned to that in the rest of the metropolis, and more particularly to that in the immediately surrounding districts, that we must seek more narrowly and locally for some peculiar conditions which may help to explain this serious visitation.

The considerations involved in this part of the inquiry may be discussed under the following heads:--Elevation of site; soil and subsoil; surface and ground plan; streets and courts; density of the [39/40] population; character of the population; internal economy of dwelling-houses, as regards light, ventilation, and general cleanliness; cesspools, closets, and house-drains; sewerage; and water supply.

Elevation of site.--As shown in the Table at page 55, the mean elevation of St. James's parish above the Thames high water mark is 58 feet, whilst that of the Berwick Street and Golden Square districts respectively is 65 and 68 feet.

The highest point in the parish, about 75 feet, is near the junction of South Row with Marshall Street, situated in the last named district. So far then from the unusual mortality from Cholera in those districts in 1854 being thus explained, it stands as the most remarkable exception to that very interesting general relation, which has been shewn by Mr. Farr to prevail throughout the metropolis, between lowness of level and a high mortality from Cholera.

According to the prevalent rule, the annual mortality from that disease in St. James's parish would not be above 40 in 10,000 persons living, whereas in seventeen weeks of 1854 it reached a registered ratio of 152; or even by taking the mean of the low rate of 1849 and the higher rate of 1854,--a proceeding which, though it serves to equalize the mortality numerically, in no way diminishes or explains the exceptional character of that of 1854,--the ratio is still 84 to the 10,000 living persons. Indeed, as is clearly shewn in the Table, the actual mortality was greatest in the [40/41] highest quarter of the parish, largely exceeding that of immediately adjacent districts which have a nearly corresponding elevation, and reducing the Cholera area of St. James's to a level with Bermondsey which has a mean elevation corresponding with the high water mark. (Compare the Table, p. 55.)

In the epidemic of 1849, similar exceptions to the general rule were instanced in St. Giles's (Holborn) and in Bethnal Green, but none of so extra-ordinary a character as that now under consideration; and, full allowance being made for the acknowledged irregularities in the local distribution of successive visitations of Cholera, this fact alone would suggest the existence of some special localizing condition.

Soil and subsoil.—Beneath the artificial or made soil of from 8 to 12 feet thick, which, as is usual in districts long covered with houses, is composed principally of accumulated rubbish charged with various débris, the natural subsoil of the entire parish is gravel, forming part of the gravel bed which extends in a westward direction through Hyde Park. Towards and at the bottom of the gravel, which varies from 20 to 30 feet in depth, are veins or layers of sand resting upon the London clay and abundantly charged with water.

This gravelly substratum insures a good natural drainage of the surface-soil and of the basements of houses, and is of course favourable to the salubrity of the district.

It should here be mentioned that the ancient [41/42] pest-field used by the neighbouring parishes, in the time of the Great Plague, had its locality east of Regent Street and north of Golden Square. As considerable doubt and error still prevail in regard to the site of this field, a slight digression may be permitted, in order to settle a subject both of medical and topographical interest. 1

The history of this pest-field is associated with the name of William, the renowned Earl of Craven, the same who fought under Gustavus Adolphus, was married, it is said, to Elizabeth, daughter of James I and Queen of Bohemia, and, having lived through troublous times, reluctantly surrendered, at the head of the Coldstream regiment, the protection of St. James's Palace to the Dutch Guards of the Prince of Orange. This remarkable man, who died in 1697, at the great age of 88, continued to reside at Craven House, Drury Lane, throughout the whole time of the plague in 1665-6. He first hired and then purchased a field on which pest-houses (said to be 36 in number) were built by him for persons afflicted with that disease, and in which a common burial ground was made for thousands who died of it. In 1687 the Earl gave this field and its houses in trust for the poor of St. Clement's Danes, St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, St. James's West-[42/43]minster, and St. Paul's Covent Garden, to be used only in case of the plague re-appearing; and the place came to be known as the Earl of Craven's Pest-field, the Pest-field, the Pest-house-field or Craven-field. In 1734, the surrounding district having become covered with houses and streets, a private Act, 7th George II., c. 11, discharged this pest-house-field from its charitable trusts, transferring them without alteration to other land and messuages at and near Byard's Watering Place, (Bayswater) Paddington, now called Craven Hill. This Act refers to the original conveyance for a description of the abutments and boundaries of the field, states that it contains three acres, more or less, and mentions, as belonging to it, "one way or passage of sixteene ffoot wide . . . to and from the premises by the Slaughter-house there leading into Eyre Street."

The original extent of the Craven Estate, so far as it corresponded with the site of the pest-field, is correctly shewn in the map prefixed to this report. Some additional property lying between West Street and Carnaby Street, purchased by Lord Craven in 1774 has nothing whatever to do with the ancient pest-field. Moreover a small portion of the northeast part of the field itself no longer belongs to the estate, having been first rented and subsequently purchased by St. James's parish as a burial ground. The present Public Baths and Wash-houses are built over the greater part of this portion. The width [43/44] of the pest-field, from the middle line of Marlborough Row and West Street to the west side of Dufour's Place, is about four chains [244 feet]; its length from the top of Brown's Court, at the back of the premises in part of Great Marlborough Street, to the set-off against No. 4, Marshall Street, is rather less than eight chains [488 feet]; so that, including the part sold to the parish, it contains three acres and a fraction, forming a tolerably exact parallelogram twice as long as it is wide. The short narrow piece of Marshall Street, next to Silver Street, (although now 18 feet wide,) undoubtedly corresponds with the way or passage mentioned in the Act, for in what appears to be the original trust deed now existing in the Craven office, this way is described as excepted out of the premises abutting the pest-field on the south, and the "Eyre Street" mentioned was probably an extension of Air Street running northwards to join Silver Street near the point in question, before Golden Square was built. In an early and perhaps unique impression of Blome’s Map of St. James's parish (one of the series to illustrate Strype’s edition of Stowe) which is now in the possession of Mr. Crace, the pest-field is shewn with a passage leading to it on the south from Silver Street, Golden Square being also laid down. The date of this map is probably 1680-90. The field itself is represented as if covered with grass, excepting a roadway which extends from the entrance-passage nearly to its northern boundary. On the east of [44/45] this roadway, about two-thirds of the distance up, the pest-houses are shewn, probably in a conventional manner, as a single block of buildings. In a later impression of this map, printed in 1720, the houses, grass and roadway are all scraped out.

From this description and the plan [map] it will be seen that at the present moment nearly the whole of Marshall Street, South Row and a part of Broad Street, traverse the old pest-field; whilst West Street and Marlborough Row occupy a strip of its western edge. Considerable doubt exists as to the precise part or parts of the field in which the burial pit or pits were dug. In quite recent times evidences have been met with in two spots, one the site of Craven Chapel, the other in the right hand lower corner of the former field, which would seem to indicate at least two places of burial. The latter position corresponds with Maitland's statement that "at the lower end of Marshall Street, contiguous to Silver Street, was a common cemetery, in which thousands of corpses were buried in the time of the plague;" whilst Craven Chapel stands on part of the open ground of the old Carnaby Market, a space which for some reason was long unoccupied by any building, though houses had been built on other portions of the field, and which open ground was styled the Pest-field up to the time of Craven Chapel being built.

It has been often alleged that in some way or other the remains of decomposing animal matter, [45/46] or indeed of the plague matter itself, lying in the soil of this district, are chargeable with the great mortality from Cholera near it. Popular opinion has even gone so far as to maintain that the disease of last autumn was not Cholera, but a direful kind of black fever. But it is scarcely conceivable that any specific poisonous agent should remain undecomposed in the ground for 200 years; and it is improbable that animal matters, generally, enclosed for so long a period in a gravelly soil should retain noxious qualities of any kind. Yet the possibility of this latter contingency cannot be absolutely denied. Supposing it to be so, such substances could only act by tainting the air directly, in consequence of the disturbance of the soil, or indirectly through the leakage of gases or fluids into the sewers; or they might otherwise act by contaminating the well-waters of the neighbourhood.

Deep cuttings made in laying down new sewers were carried through one part of the old pest-field in 1851 (as shown by the blue colour), and through other parts (as indicated by pink colour) in the winter of 1853-4, the last-named works being completed in February 1854; but no evidence exists of either line having passed directly through an ancient plague-pit; no serious nuisance occurred at the time the ground was opened; and no immediate ill consequences ensued to the health of the surrounding inhabitants. It is well known that the whole of the pest-field was not used as a burial place; and, as [46/47] it happened, the cuttings for the new sewers passed through a fine gravelly soil. Moreover, an interval of at least seven months occurred between the period at which the earth was broken up and the outbreak of Cholera which was imagined to have been thus produced; and, it may be added, the site of the pest-field comprises but a small part of the "Cholera area," and was not more severely visited than other quite distant parts of it.

In reference to the opinion that the sewers themselves may have become channels of contamination by the passage into them of gases or fluids from the pest-field soil, it must be remarked that percolation of any kind would be very unlikely through sewers so newly constructed; at all events, this would have taken place much more easily through the older and more decayed ones, and yet in 1832 and 1849, although Cholera penetrated the district, no unusual outburst took place; moreover, as will be subsequently explained, the drainage from the pest-field flows in two definite directions, whilst the aggravated effects of Cholera were equally felt along other lines of sewers.

As regards the possible contamination of the well water by the fluids of the pest-field, it must be remembered that, in the numerous excavations which have been made in its soil from time to time for the foundations of houses, in sinking wells, and in cuttings for sewers, drains, gas and water pipes, not only must much of the actual plague deposit [47/48] have been removed, but the soil has been so perforated and channeled that for many generations past, in addition to the natural drainage which is very perfect, it has been draining itself continually in these artificial ways and so ridding itself of its noxious contents. Hence the chances of the contamination of the well water by the pest-field fluids would become less and less every year, and would certainly be greater in 1832 and 1849 than in 1854. Even the older sewers have been known to rob the water supply from certain wells, and the new cuttings, being of greater depth, must act still more efficiently to relieve the soil of any impure fluids with which it may be charged.

On the whole, the supposition of the injurious influence of the pest-field as a special cause of the Cholera outbreak in St. James's, is not supported by any important facts.

Surface and Ground Plan.--With the exception of St. James's and Golden Squares, Burlington Gardens, part of the Church Yard and the Workhouse Green, every spot in St. James's Parish is either covered by buildings or more or less perfectly paved; and it is hardly necessary to add that there are no open ditches, ponds or stagnant waters, and no pieces of habitually damp ground. The surface is least occupied by houses in the St. James's Square district; more so in the Golden Square; most of all in the Berwick Street district.

Streets and Courts.--In the St. James's Square [48/49] and Golden Square districts there are many long, direct and wide streets, but in the Berwick Street and contiguous parts of the Golden Square district most of the streets and courts are comparatively narrow, short and exceedingly intricate in their arrangement. Some of the streets even have a dead wall across one end; whilst, of the greater number of those which have a thoroughfare both ways, the junctions with each other are at such irregular intervals that they appear to be obstructed, the view either way is exceedingly limited, and the neighbourhood is very perplexing to a stranger. Even so considerable a street as Broad Street presents no direct outlet at either end. Out-of-door ventilation along the streets is seriously impeded in such a neighbourhood. The heart of the district is much protected both on the east and on the west,--the quarters from which the prevalent winds of this country blow. In calm weather the stagnation of the street atmosphere must be almost complete. Indeed, during the hot still days at the end of last August, this was painfully felt and noted by many of the inhabitants. As a special instance, it may be mentioned that the persons residing in Pulteney Court and New Street complained of feeling suffocated by the temporary closing of Cock Court, during the erection of the model lodging houses named Ingestre Buildings.

Lastly, it must be noted, as touching this question of out-of-door ventilation, that in the district now under consideration, the yards to the houses are [49/50] generally very small, and all available spaces behind the dwellings are covered with factories, workshops or small tenements or cottages,--all offering further impediments to a proper circulation of air outside the houses.

Density of Population.--From the close covering up of the surface which has just been described, it might be expected that this part of St. James's would be very densely peopled. The fact is so to a startling degree. The entire parish in 1851 had a population of 222 persons to an acre, standing in this respect within three of the top in the list of the 36 registration districts in the metropolis. The sub-district of St. James's Square had a density of 134 per acre; that of Golden Square 262; whilst the Berwick Street sub-district had a population of 432 persons to an acre, being actually the most densely crowded of the 135 sub-districts into which London and its suburbs are divided.2 The removal of the block of houses between Hopkins’ Street and New Street, for the erection of Ingestre Buildings, which were incomplete at the time of the Cholera outbreak, would somewhat reduce the population [50/51] in the Berwick Street sub-district in 1854. The relatively smaller population in the Golden Square district is accounted for by its including Golden Square, the whole width of Regent Street, Great Marlboro Street, the Earl of Aberdeen's, the Pantheon, and the Workhouse Yards; but there are parts of it contiguous to the Berwick Street sub-district, and comprised within the Cholera area, which are quite as densely crowded as the latter; and, since all parts are not equally overcrowded in either, the high rate of the population per acre implies a much greater concentration of the evil in special localities.

Character of the Population.--Confining our attention now to the district particularly affected by the Cholera, it may be stated, in general terms, that the great mass of the persons inhabiting the densely crowded parts is composed of the families of labourers, mechanics and journeymen (many of them tailors), of persons, in short, employed at fair wages and manifesting no peculiarity in moral characters, habits or occupation beyond those usual to their class.3 The number of those who live other-[51/52]wise than by industry is certainly small. Besides the residents in this crowded district there is a daily influx and efflux of probably 2000 persons engaged within it in various workshops and factories in none of which however are any specially injurious processes carried on. The larger and less crowded streets are occupied by tradespeople and the professional classes, in every way corresponding with those of similar neighourhoods.

Dwelling Houses,--internal economy as to space, light, ventilation, and general cleanliness--For the most part the houses in this district are old, having been built about the years 1700 to 1740. As already stated, the yards are very small and much covered, but there are no houses built back to back. In some streets the houses are what are termed 3rd class houses, containing from 10 to 15 rooms. In the smaller streets they are 4th class houses. The rooms of course vary in size and height, and, as usual in dwellings constructed 150 years back, are not objectionable unless over-filled with inhabitants. Cellars and vaults are common; the front areas are narrow and much covered in. Of light there is, generally speaking, an abundance, as the numerous windows, constructed before the adoption of a Window Duty, have been re-opened since its abolition. The indoor ventilation is, on the whole, defective, the staircases and passages being [52/53] narrow, and the sashes, with some exceptions, being single-hung, so as to open only at the bottom, a serious defect which cannot be too strongly condemned. Probably not more than a dozen houses in the affected district are occupied by a single family, the sub-division of one dwelling among many families being the rule. The competition for rooms has been so great that a respectable workman can often only afford to have one for his whole family. The underground rooms or kitchens are frequently inhabited; in Broad Street, for example, in nearly two out of five houses; in many of the smaller streets, half of the kitchens are occupied as dwelling and sleeping rooms, sometimes by a numerous family; but more commonly the number of persons in each kitchen is small. The ground floors of more than half the houses are occupied as shops. The population, taken generally throughout the district, is accumulated rather in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd floors [2nd, 3rd, and 4th floors in U.S. parlance], the 2nd floor being usually the most densely peopled. In Broad Street the average number of persons to a house is about 18, and to each floor 5½. But the greatest differences prevail, for even in Broad [S]reet there are instances of 30 persons living in one house; in one of the smaller streets 54 persons were crowded into one dwelling. The unusual overcrowding of certain houses follows from the general statistics already detailed. In the "Cholera area" the ratio is between 17 and 18 persons to each house.

Now, in the close and complicated streets, in the [53/54] densely packed dwellings, in the climax of overcrowding as compared with all London, in the character and occupations of the people and in the general economy of the houses, conditions are found which, with other necessarily attendant evils, might be supposed to neutralize the advantages arising from the nature and elevation of the soil. Such an explanation indeed has already been offered by Dr. Baly in regard to the comparatively high rates of mortality from Cholera observed in Bethnal Green and in St. Giles' Holborn. Within very straitened limits and with unfavourable external conditions, there is certainly to be found in the Cholera area of St. James's a large number of that very class of persons,--labourers, mechanics, artisans, journeymen, and tradespeople,--who usually supply the most victims to the disease. But that this circumstance, combined even with defective domestic arrangements, is adequate to explain the actual outbreak, appears doubtful; or why was not the presence of the Cholera agent in this same district in 1832 and 1849, although then equally overcrowded, attended by the same lamentable consequences; and why did not Cholera, which was present at the same time under the same meteorological conditions and with closely corresponding local circumstances, in the adjoining districts, ravage them to the same extent? In All Souls Marylebone, in St. Anne’s Soho (excluding St. Anne’s Court), in St. Giles’s, and in parts of St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields, nearly similar spots could be pointed out; yet, as [54/55] shewn by the annexed Table, the mortality in each was, compared with that of St. James’s, very low.

[55/56] In certain instances within the Cholera area the mortality bore a direct relation to the density of the population. This is true chiefly of streets in the centre of the district, for towards its borders an overcrowded people, with defective external and internal ventilation, and a large amount of general uncleanliness, did not suffer in the same degree as in the lower part of Wardour Street, in Peter Street from No. 20 to 32, in Walker's Court and in Little Pulteney Street. Individual instances of extreme uncleanliness in both streets and houses, as No. 7 Husband Street, were sometimes associated with comparative immunity from the disease; whilst some of the wider streets and well-ordered and scantily filled residences were visited severely. It has already been mentioned that 7 workmen engaged in the open air, in the erection of Ingestre Buildings, died; at least 30 other non-residents, visitors or workmen, besides about a dozen others who merely came to dine at chop or coffee-houses in the district, also died; yet none of these persons slept in it, or could have been much influenced by its permanent conditions. Lastly, as bearing on this subject, it must be noted that the average annual mortality of the Berwick Street and Golden Square sub-districts from all causes of death, is by no means high (see previous Table), shewing that no serious results ordinarily ensue from the acknowledged sanitary defects just described. The elevation is probably the chief cause of this general healthiness.

Finding then that the evils necessarily attending [56/57] the most densely crowded population within the circle of metropolitan registration do not offer a clear and decided explanation of the aggravated results of Cholera in this parish, we pass to such other local sanitary disadvantages as might or might not accompany this overcrowding and so be obnoxious or otherwise to health, viz. the state of the cesspools, house-drains, sewers, and water supply.

Dust-bins and accumulations in yards, cellars and areas.--At the time of the visitors’ inquiry very careless arrangements were still found to exist in regard to these points, and at the period of the Cholera visitation there were undoubtedly many nuisances of the kind; but on the best authority it may be stated that Cholera was most impartially distributed between the comparatively dirty and comparatively cleaner spots.

Cesspools, closets and house-drains.--The visitors’ inquiry lists sufficiently prove the insuperable difficulty of arriving at true results as to the existence or absence of cesspools. There is every reason to believe that they exist in large numbers. Originally such receptacles would be sure to be provided, and, as an illustration of the abundance of these obnoxious pits in certain parts of the parish, it may be mentioned, on the authority of the late Sir H. de la Beche, that when Derby Court, Piccadilly, was pulled down to clear a site for the Museum of Economic Geology, no less than thirty-two cesspools had to be excavated.

Such cesspools are frequently situated in the [57/58] narrow front areas, kitchens or vaults, there being generally no space available for such conveniences in the backyards. In the event of any obstruction or overflow the entire basement must therefore be filled with deleterious substances or gases. These cesspools are generally connected with the sewers by means of flat-bottomed brick drains, having, in some cases, the advantage of a bricklayer’s water-trap in the area or vault. Of the faulty construction of these drains and traps, and of the defective state of repair and blocked-up condition of many of the cesspools, little doubt can exist after the discovery of all those defects in the inquiry conducted by Mr. York at No. 40 Broad Street. The house-drains themselves are also of considerable age and are probably in many cases in the decayed condition detected on the same premises.

Equally impossible is it to ascertain, without additional powers of search, the mode in which these house-drains are connected with the sewers; but it may safely be stated that for the most part it is by a simple outlet or drain-mouth, without other trapping than the water-trap in the area. Frequently, when the original sewers are replaced by new ones situated at a greater depth, this opening is made near the top of the sewer arch instead of towards the bottom. In some houses, but certainly in the minority, water-closets with pipe-drains and leaden air-tight flaps are substituted for the older arrangements.

Sewers.--Owing to successive alterations and ad-[58/59]ditions the sewerage of the district affected by the Cholera is arranged in a rather complicated manner. Its plan, as it existed in the autumn of 1854, is laid down in the map prefixed to this Report, constructed on the authority of the one published in Mr. Cooper’s Report to the Metropolitan Commissioners of Sewers. The older sewers, some of which were built as late as 1823, are left uncoloured; a new sewer constructed in 1851 is shaded blue; whilst the late extensive additions made in the winter of 1853-4 are tinted pink. The several systems appear to work as follows:--

a. Waterflow. 1. Starting from the high ground near the junction of South Row with Marshall Street there is a fall in the sewers in two directions, so that the drainage from the upper part of Marshall Street, South Row and all the intermediate courts and streets to Carnaby Street flows westward through Tyler Street and Foubert’s Place into the Regent Street sewer. 2. On the other hand, the middle third of Marshall Street, from South Row to Broad Street, Broad Street itself (including Dufour’s Place) as far as Cambridge Street, Cambridge Street and the two Windmill Streets, form another line of flow, running south, east, and then south again. 3. The eastern half of Broad Street, Poland Street, Berwick Street and its dependencies, Pulteney Court, and all the small streets and courts east and south as far as Wardour Street and Little Pulteney Street, ultimately run into the Wardour Street [59/60] sewer. 4. The short piece of sewer in the lower part of Marshall Street, south of Broad Street, ends in a transverse line which follows Silver Street, and from a point opposite to Bridle Lane falls in two directions, westward to join the Golden Square sewers through Upper James Street, and eastward by a pipe-drain to end in the Cambridge Street line already mentioned. 5. Great Pulteney Street has a sewer to itself, running south into a second transverse line which occupies Brewer Street and Little Pulteney Street and, crossing above the Windmill Street line, falls both ways from that point; viz. westward into the Golden Square system and eastward into the Wardour Street sewer.

b. Atmospheric connection.--Of the five systems of sewers just described the first (pink) has atmospheric connection with the second (blue) at the high level in Marshall Street near the end of South Row. The first and third appear to be connected atmospherically by the Great Marlborough Street line. The fourth (Silver Street) is connected with the second at the junction of Cambridge and Little Windmill Streets, and with the fifth (Brewer Street) through the Golden Square sewers. The fifth is further connected with the third (Wardour Street) at the end of Little Pulteney Street. Lastly, the second and third, occupying respectively the two halves of Broad Street, have only an indirect and circuitous atmospheric connection.

At the period of the Cholera outbreak it was [60/61] very generally believed that the unusual mortality was in some way or other chiefly attributable to the sewers themselves or to their alteration and extension in certain parts of the district in 1851 and in the winter of 1853-4. 1st, because of the disturbance of the ground of the old pest-field already alluded to; 2ndly, because of the general disturbance of the artificial soil, the removal of good gravel and the subsequent filling in with rubbish; 3rdly, on account of sundry diversions or changes in the previous current of the drainage; 4thly, because of the foul and loaded condition of the sewers, and the escape of noxious air from the numerous ventilators and untrapped gullies.